David Elia trained as a designer but has in last years focused more on painting and drawing. Still there’s much that connect his paintings and his design objects, he brings a keen interest in the environment, history and social questions into his work abstracted into grids and dots. Rob Goyanes is a writer and editor from Miami, Florida, living in Los Angeles. He works as an editor for book publishers, popular and unpopular magazines, fiction writers, artists, curators, and music labels.

Rob Goyanes Let’s talk about your studio in Monaco — you have a lot of design pieces in the space.

David Elia I collect mid-century design: Scandinavian, Italian, French. I get a lot of inspiration from that era. There’s a theme when I collect, it’s really about nature, organic materials, shapes. I’m really attracted to geometry and mathematical elements too.

Q It helps to be surrounded by beautiful objects.

A It really appeals to me, the decorative aspects of contemporary and modern art. I look a lot at the Pattern and Decoration movement, as well as color field painting. I recently discovered the work of Alma Thomas from the Washington Color Field School, which really spoke to me.

Q I’m curious about your personal relationship with the forest. Growing up in Rio in the 1980s and ’90s, what was the cultural attitude toward the forest at that time? How did it impact your sense of self and aesthetics?

A When you’re in Rio, you’re completely immersed in the tropical environment. It’s very exuberant. As a kid I was always playing outside, I’m a very outdoors person. My friends, all their homes were in the middle of the forest. There were constantly forests all around me. I left Rio for the South of France when I was 7 years old. I would go back once a year, we still had a home there and some family and close friends. Having those two sides of the environment really informed my work in different ways. We visited the South of France a lot. I recognized the special light there that artists often talk about. Cezanne and Matisse always spoke about how the light was very conducive to their work, that luminous quality. The light in Rio, it’s a different kind of light, it’s stronger, yet the sky is much darker. The light that interacts with the green of the forest is so strong that the sky becomes even more blue, a very strong blue

Q Your recent work includes cyanotype photography, depicting the Amazon forests. What does that medium accomplish that others can’t? How does the history of this technology tie into the place?

A The works on paper are representational, they’re photos of the forest using the cyanotype. It’s the idea of a portal into the forest. The iconography of the 19th century, those European botanists and artist-adventurers who went there, that’s what I was trying to evoke through those pictures. They also have a theatrical aspect which I find interesting. In the abstract dotted paintings on canvas the colors all belong to Werner’s Nomenclature of Colors. Each color was taken from a specific element found in nature by Abraham Werner, a 19th century German mineralogist. It was interesting to integrate that with the cyanotype. I apply the cyanotype the way paint is applied to canvas. It allows me to play with positive and negative space, by placing masking tape, or grids, on top of them. It allows me to build up layers.

Q Dots, grids, and other patterns show up often in your art.

A For me, the dots represent a topographical view of the forest canopy. It’s how one would draw a tree from the top at its most basic shape. Looking at landscape architecture is critical to my work. One of my degrees was in architecture, so that influenced me a lot, the discipline’s technical aspects. I get inspiration from patterns from all over the world: the Aztec Nazca lines, aboriginal and African art and patterns. I’m also inspired by patterns from the Marajoara culture, a pre-Columbian civilization that existed in the Amazon.

Read the full interview here.

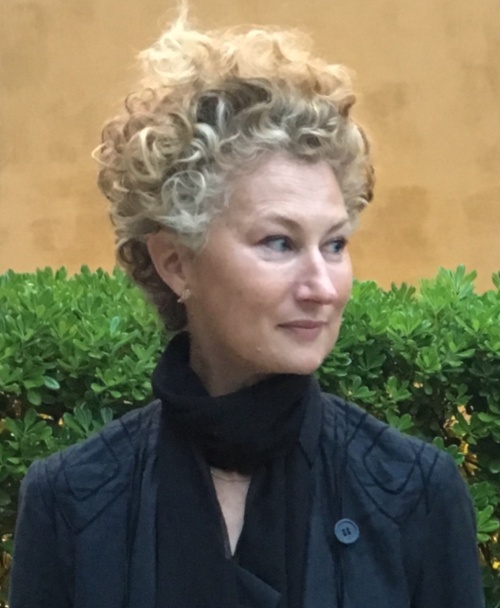

David Elia's studio